Bishop Robert Barron – Transcript (non-verbatim), Holy Thursday Mass on March 28, 2024

Well, again, everybody, a great joy to be with you as we begin this most sacred time in the church year.

Probably a lot of you know that I’ve got a great devotion to St. Thomas Aquinas. When I was over in Rome, for the Synod last October, I very happily played hooky one day toward the end of the Synod, and left with a friend of mine, a Dominican friend, to go down to Naples. Our destination was the church of San Dominico, the great Dominican church in Naples, which Aquinas knew back in the 13th century. In fact, he had a cell there. Well, we said Mass in a side chapel of San Dominico, which is very famous because something extraordinary happened to St. Thomas Aquinas in that chapel. Thomas, at that point in his life, was writing the last section of his famous Summa Theologiae, his great masterpiece. He just finished the section on the Eucharist to which he had this great devotion. Even though it’s recognized as a masterpiece of the theological tradition now, Thomas Aquinas felt he had not done justice to the beauty and truth of the Eucharist. Dramatically, he took the text itself, they say, and he put it at the foot of an icon of the cross of Jesus, you can still see it there, and he prayed in front of it as if to ask the Lord’s judgment on it. They say a voice came from the cross. The voice said, “Bene scripsisti de me Thomma. Well, have you written of Me, Thomas; what would you have as a reward?” Aquinas responded, “Non nisi te domine. Lord, I’ll have nothing except you.” I made that my Episcopal model because from the time I heard that story I thought that answer was so moving. What would you have as a reward for this great achievement? Lord, I’ll have nothing except you.

Go back about 10 years before that event, and now the 1260s, Aquinas finds himself in Orvieto. If you’ve been over there, it’s about an hour north of Rome by car. Charming little town. He was there because the Pope was there, and Thomas was part of his entourage in those days. Well, while he was in Orvieto, the famous miracle of Bolsena took place there. Bolsena is a little town not far from Orvieto. There was a priest who had come from Northern Europe, on a pilgrimage to Rome, he’s on his way. He was going through a crisis of faith around this question of the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. So, while this priest was in Bolsena saying Mass, he elevated the consecrated host, and blood ran from the host onto his hands, and then from his hands onto the corporal of the altar.

Well, he was so amazed and shocked by this that he and some friends took that Corporal that was stained by blood, and they raced to Orvieto to show it to the Pope. The Pope was so impressed that he decided to institute a new feast in the life of the church, which is still celebrated to this day, called the Feast of Corpus Christi of the Body of Christ. In fact, we’re going to celebrate it June 2 up in Rochester with a great festive liturgy.

The pope institutes the feast. He says now I need texts—I need hymns, I need texts and prayers for this feast. So, he turned toward this brilliant and mystical Dominican, Thomas Aquinas, and said would you write for me the texts for this feast of Corpus Christi? Thomas Aquinas, who loved the Blessed Sacrament, writes another masterpiece, the hymns and texts for Corpus Christi. The most famous of these we’re going to sing later on today at the very end of our celebration. It’s sung to this day all over the church around the world. It’s called the Pange Lingua. What I want to do is just look at a few lines of this famous hymn because in it is Aquinas’ doctrine of the Eucharist, and in many ways, the most beautiful elements of the Church’s faith in the Blessed Sacrament.

Here’s how it starts:

Pange, lingua, gloriósi córporis mystérium

Sing my tongue of the glorious mystery the body.

How wonderful that tonight, especially as we celebrate the Eucharist, we sing and we chant, and we have processions and we have ritual, and we have incense rising. It’s as though this sacrament is so profound in its mystery that even the most acute words of a theologian such as Thomas Aquinas, couldn’t begin to approach it. Rather the best we can do is we can sing. And the Church has been doing that song now for the past 2000 years.

Here’s how the second verse begins:

Nobis datus, nobis natus Ex intácta Vírgine.

Given to us, born to us from the Immaculate Virgin.

It’s a very interesting connection, everybody, between Mary and the Eucharist. When the second person of the Trinity took to himself a human nature, he got his flesh and his blood from the Virgin Mary. What’s the Eucharist, but the flesh and blood of Jesus, and therefore you can’t adore the Eucharist without being mindful of Mary. You can’t be mindful of Mary without being led to the Eucharist. Aquinas knew that; the Church has known that in its faith.

This next verse begins and keep our first reading from Exodus in mind:

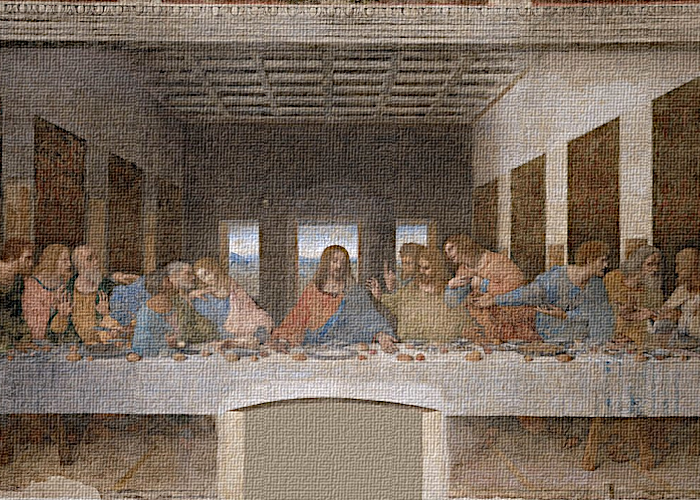

In suprémæ nocte coenæ recúmbens cum frátribus.

In the night of the Last Supper, reclining with his brothers.

The lovely ambiguity in Latin in the “suprémæ coenæ,” it means the Last Supper, but also the supreme supper. In the night of that unsurpassable supper, “recúmbens” reclining with his brothers. What does he do? He observes all the laws of the old law. Did you listen—out of the book of Exodus, we heard about the Passover. This great event by which a lamb is slaughtered. It’s blood provides protection from death. The lamb is sacrificed and then the lamb is consumed. This is what’s repeated in every Passover, in fact, in Jewish households to the present day.

Jesus, the night before he died—yes, recúmbens cum frátribus, reclining with his brothers, the first priests—follows all of the laws of Passover, calling to mind the sacrifice lamb. But then, listen: “Cibum turbæ duodénæ se dat suis mánibus.” He gives to his 12-fold band, that’s the apostles, suis minibus, by his own hands himself to eat. Yes, it’s a Passover supper, but it’s not just a lamb who has been sacrificed, not just the lamb whose blood provides protection, not just the lamb that they eat. It’s Christ himself who is the sacrifice, Christ’s own blood that protects us from sin and death, and Christ’s own body that becomes food for us.

How does this happen? This is the faith of the Church we know. How does it happen? Listen now to the next verse: “Verbum caro, panem verum verbo carnem éfficit.” Verbum caro, the word made flesh. That’s Jesus. Not one more prophet, if that’s all he is, the heck with him. Not just one more teacher, if that’s all he is, who cares? Verbum caro, he’s God’s word made flesh. And what does he do? He changes true bread by his word into true flesh.

Now, we’re right at the pivot point of the mystery here. Have you noticed that our words, our puny little human words, can affect reality. Some words just describe reality. If someone asked me tomorrow, hey, what was the Mass like last night at the Cathedral? I could say, oh there were so and so people here, and it was this and that. My words are just describing what’s happening. But sometimes, isn’t it true, our words can affect reality? You can say something so wounding to a person that they’re affected for the rest of their lives. By the same token, you can say something that’s so inspiring, that’s so uplifting, that it changes someone permanently. Okay, if that’s true of our little puny words, what about God’s Word? In the beginning was the Word, and through that word all things came to be. God said, Let there be light and there was light. God said, let the dry land come forth, and so it happened. God’s word affects reality at the deepest level. God’s word makes things to be. Now, verbum caro, the word made flesh… that’s Jesus. This is why when he says to the dead girl, Talita Cumi, little girl get up. Well, by God, she gets up. That’s why when he says to Lazarus, four days in the tomb, Lazarus come forth, he comes forth by God, because what Jesus says is, what Jesus says happens.

The night before he died, recúmbens cum frátribus, reclining with his brothers at the Passover supper, he says over the Passover bread, This is my body; and over the Passover wine, This is the chalice of my blood. A symbol, if that’s all it is, who cares? No, what Jesus says is, because he’s the verbum caro, he’s the word made flesh. What he says, is. What he says reaches to the deepest roots of the being of things and makes them what they are. That’s why our friend Thomas Aquinas talks about Transubstantiation: the very substance, the depth, the reality of the bread and wine change into the body in the blood of Christ. It’s by the power of the word that it happens.

Just one last step. Here’s the verse we all know and we’re going to sing it later tonight:

Tantum ergo sacramentum venerémur cérnui.

We venerate, we worship, bowing down, therefore such a great sacrament.

We bless the water of baptism that the priest or bishop uses to baptize. Would you ever dream of bowing down and worshiping the baptismal water? I wouldn’t. We bless the oils, I did it the other day at the Chrism Mass. We bless the oils that are used at confirmation and ordination. Would you ever dream of bowing down and worshiping that oil? No.

Thomas Aquinas said in the other sacraments, the vertus christi is present. That means the power of Christ. That’s true the power of Christ is operative in the waters of baptism and in the oil of confirmation. But, says Aquinas, in the Eucharist, ipse Christus is present. That means Christ himself, not just his power, ipse Christus, Christ Himself is present, which is why Venerémur cérnui. That’s why bowing down, we adore, and we worship the Eucharist.

See, friends, that’s what tonight really is all about as we begin the triduum, and we focus on this indeed blessed sacrament. The sacrament, which is the source and summit of the Christian life; the sacrament, which is the beginning and the end of our faith; the sacrament, which is not just the vertus christi, but ipse Christus, Christ himself. That’s what we’re doing with all these rituals, all these gestures, all these words, all this song. What we’re doing is we’re adoring Christ really present. Christ’s greatest gift to us: his Church.